Macron’s Europe

Alongside Germany, France has often shaped the EU’s agenda. Recently, French influence has grown, and if President Emmanuel Macron is re-elected in April 2022 – likely, though not certain – he will be Europe’s pre-eminent leader for several years.

One reason is that Macron is brimming with ideas on the future of Europe, which he pursues energetically. The Brussels institutional machinery feeds off ideas. Macron’s predecessor, François Hollande, came up with fewer schemes and initiatives and was a quieter voice in the European Council.

A second reason is Brexit. The UK led the EU’s economic liberals in resisting France’s penchant for protectionism and an active industrial policy. Now the Dutch sometimes try to lead the Nordic, Baltic and other pro-market countries, but with less authority than did the British.

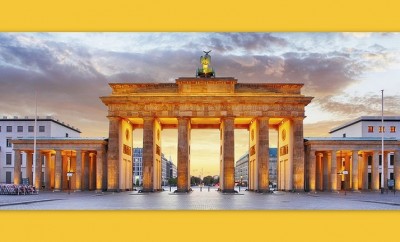

A third reason is Chancellor Angela Merkel’s impending retirement. Her track-record in crafting compromises helped to make her the European Council’s most respected leader. Germany is already distracted by the campaign for September’s general election, after which the formation of a new coalition government may take two or three months. Then the new chancellor – whether Armin Laschet or Annalena Baerbock – will need time to establish themselves as a substantial figure in EU politics.

So, if Macron wins re-election, he will have more heft than the new German chancellor. The economic and political travails of Italy and Spain limit their influence, and in any case both quite often line up with France on EU policy. Poland is in trouble for not respecting the rule of law and so cannot set the EU’s agenda.

France will use its EU presidency in the first half of 2022 to promote its ideas on Europe. Fortunately for Macron, many of the key people in Brussels are sympathetic to France. Ursula von der Leyen, the Commission president, Charles Michel, the European Council president, and Josep Borrell, the High Representative for foreign policy, owe their jobs to Macron’s support. They are at the very least open to French thinking. In Frankfurt the president of the European Central Bank, Christine Lagarde, happens to be French. So are some important officials in Brussels, including Thierry Breton, the commissioner for the internal market, and Olivier Guersent, the director-general for competition policy. In the European Parliament, too – which France has previously not taken very seriously – the French have become more influential. Macron’s MEPs are the largest component of the centrist Renew Europe formation, one of the three groups that run the Parliament.

Συνέχεια ανάγνωσης εδώ

Πηγή: cer.eu