Early Italian economic warning signals

Anyone who thinks that the Euro crisis is over has not been paying attention to recent financial market developments in Italy, the Eurozone’s third largest member country with an economy around ten times the size of that of Greece. Nor have they been taking note of the growing “doom loop” in the Italian banking system as these banks add to their already excessively large holdings of Italian government bonds.

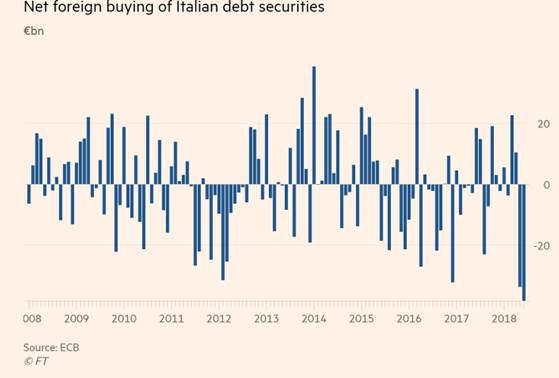

One of the more striking financial market developments since Italy’s March 2018 election has been the flight of foreign investors from the Italian government bond market. Fearing the direction of the Italian economy under a populist-led coalition government at a time that the country still has a massive public debt mountain and the shakiest of banking systems, foreigners have been reducing their Italian government bond holding at a rate of around EUR 40 billion a month. That withdrawal has been at a greater rate than that in 2012 at the peak of the Eurozone debt crisis.

Needless to add, the withdrawal of foreigners from the Italian bond market has led to a sharp increase in Italian government bond yields. Over the past year, the yield on 10-year Italian government bonds has more than doubled to 3.1 percent. This has to be of particular concern ahead of the European Central Bank’s intention to end its bond buying program by the end of this year.

It also has to be a matter of concern that it is the Italian banks that are stepping into the breach to fill the government’s financing gap left by the foreign investor flight. By so doing they are further weakening their already fragile balance sheets. At a time that these bank’s non-performing loans account for around 15 percent of their balance sheet, and at a time that these banks are already holding around EUR 350 billion in Italian government bonds, one would think the last thing these banks needed to do was add to their already excessive Italian government bond holdings.

One has to hope the new Italian government is heeding the clear warning signals being sent to them by the Italian bond market vigilantes. Maybe then that government will be less inclined to deviate from the budget discipline being required of it by its European partners. Similarly, maybe then it will be less likely to roll back the market friendly economic reforms of its predecessor. Such policies might give the Italian economy a chance to grow out from under its present public debt mountain.

If the Italian government does not heed the market’s warning, we should brace ourselves for another round of the Eurozone debt crisis. Bearing in mind that, after the United States and Japan, Italy has the world’s third largest sovereign debt market, we should also fear that an Italian economic crisis would have real spillover effects for the rest of the global economy.

Desmond Lachman joined AEI after serving as a managing director and chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney. He previously served as deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Policy Development and Review Department and was active in staff formulation of IMF policies. Mr. Lachman has written extensively on the global economic crisis, the U.S. housing market bust, the U.S. dollar, and the strains in the euro area. At AEI, Mr. Lachman is focused on the global macroeconomy, global currency issues, and the multilateral lending agencies.